From Huffington Post

Posted: 06/01/2012 12:09 pm;

Updated: 06/01/2012 12:09 pm

By: SPACE.com Staff

Published: 05/31/2012 02:13 PM EDT on SPACE.com

The vastness of space and the puzzling nature of the cosmic objects that occupy it provides no shortage of material for astronomers to ponder.

To round up some of the most enduring mysteries in the field of astronomy, thejournal Science enlisted help from science writers and members of the Board of Reviewing Editors to choose eight puzzling questions being asked by leading astronomers today.

As Robert Coontz, deputy news editor at Science, writes in his introduction to the series, the participants decided that, "true mysteries must have staying power," rather than being questions that might be resolved by research in the near future. In fact, while some of the topics discussed may one day be solved through astronomical observations, others may never be solved, he added.

In no particular order, here are eight of the most compelling mysteries of astronomy, as presented by the journal Science:

What is dark energy?

In the 1920s, astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered that the universe is not static, but rather is expanding. In 1998, the Hubble Space Telescope, named for the astronomer, studied distant supernovas and found that the universe was expanding more slowly a long time ago compared with the pace of its expansion today.

This groundbreaking discovery puzzled scientists, who long thought that the gravity of matter would gradually slow the universe's expansion, or even cause it to contract. Explanations of theuniverse's accelerated expansion led to the bizarre and hotly debated concept of dark energy, which is thought to be the enigmatic force that is pulling the cosmos apart at ever-increasing speeds.

While dark energy is thought to make up approximately 73 percent of the universe, the force remains elusive and has yet to be directly detected.

"Dark energy might never reveal its nature," Science staff writer Adrian Cho wrote. "Still, scientists remain optimistic that nature will cooperate and that they can determine the origins of dark energy."

How hot is dark matter?

In the 1960s and 1970s, astronomers hypothesized that there might be more mass in the universe than what is visible. Vera Rubin, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, studied the speeds of stars at various locations in galaxies. [Top 10 Strangest Things in Space]

Rubin observed that there was virtually no difference in the velocities of stars at the center of a galaxy compared to those farther out. These results seemed to go against basic Newtonian physics, which implies that stars on the outskirts of a galaxy would orbit more slowly.

Astronomers explained this curious phenomenon with an invisible mass that became known as dark matter. Even though it cannot be seen, dark matter has mass, so researchers infer its presence based on the gravitational pull it exerts on regular matter.

Dark matter is thought to make up about 23 percent of the universe, while only 4 percent of the universe is composed of regular matter, which includes stars, planets and humans.

"Scientists still don't know what dark matter is, but that could soon change," Cho wrote. "Within years, physicists might be able to detect particles of the stuff."

But while astronomers may soon be able to detect particles of dark matter, certain properties of the material remain unknown.

"In particular, studies of runty 'dwarf galaxies' might test whether dark matter is icy cold as standard theory assumes, or somewhat warmer — essentially a question of how massive particles of dark matter are," Cho explained.

Where are the missing baryons?

If dark energy and dark matter combine to make up roughly 95 percent of the universe, regular matter makes up about 5 percent of the cosmos. Yet, more than half of this regular matter is missing.

This so-called baryonic matter is composed of particles such as protons and electrons that make up most of the mass of the visible matter in the universe.

"As astronomers count baryons from the early universe to the present day, however, the number drops mysteriously, as if baryons were steadily vanishing through cosmic history," wrote Yudhijit Bhattacharjee, a staff writer at Science.

According to Bhattacharjee, astrophysicist suspect the missing baryonic matter may exist between galaxies, as material that is known as warm-hot intergalactic medium, or WHIM.

Locating the missing baryons in the universe continues to be a priority in the field of astronomy, because these observations should help researchers understand how cosmic structure and galaxies have evolved over time.

How do stars explode?

When a massive star runs out of fuel and dies, it triggers a spectacular explosion called a supernova that can briefly shine more brightly than an entire galaxy.

Over the years, scientists have studied supernovas and recreated them using sophisticated computer models, but how these gigantic explosions occur is an enduring astronomical puzzle. [Gallery: Supernova Explosions]

"In recent years, advances in supercomputing have enabled astronomers to simulate the internal conditions of stars with increasing sophistication, helping them to better understand the mechanics of stellar explosions," Bhattacharjee wrote. "Yet, many details of what goes on inside a star leading up to an explosion, as well as how that explosion unfolds, remain a mystery."

What re-ionized the universe?

The broadly accepted theory for the origin and evolution of the universe is the Big Bang model, which states that the cosmos began as an incredibly hot, dense point roughly 13.7 billion years ago.

A dynamic phase in the history of the early universe, approximately 13 billion years ago, is known as the age of re-ionization. During this period, the fog of hydrogen gas in the early universe was clearing and becoming transparent to ultraviolet light for the first time.

"Some 400,000 years after the big bang, protons and electrons had cooled off enough for their mutual attraction to pull them together into atoms of neutral hydrogen," science writer Edwin Cartlidge stated. "Suddenly photons, which previously scattered off the electrons, could travel freely through the universe." [Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

A few hundred million years later, the electrons were stripped off the atoms again.

"This time, however, the expansion of the universe had dispersed the protons and electrons enough so that the new energy sources kept them from recombining. The 'particle soup' was also dilute enough so that most photons could pass through it unimpeded. As a result, most of the universe's matter turned into the light-transmitting ionized plasma that it remains today."

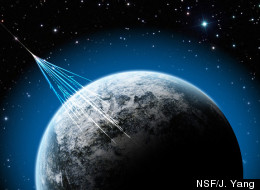

What's the source of the most energetic cosmic rays?

The source of cosmic rays has long perplexed astronomers, who have spent a century investigating the origins of these energetic particles.

Cosmic rays are charged subatomic particles — predominantly protons, electrons and charged nuclei of basic elements — that flow into our solar system from deep in outer space. As cosmic rays flow into the solar system from elsewhere in the galaxy, their paths are bent by the magnetic fields of the sun and Earth.

The strongest cosmic rays are extraordinarily powerful, with energies up to 100 million times greater than particles from manmade colliders. Still, the origin of these strange particles has been an enduring mystery.

"After a century of cosmic ray research, the most energetic visitors from space remain stubbornly enigmatic and look set on keeping their secrets for years to come," wrote Daniel Clery, deputy news editor at Science.

Why is the solar system so bizarre?

As astronomers and space observatories discover alien planets around other stars, researchers have been keen to understand the unique characteristics of our solar system.

For instance, while extremely varied, the four innermost planets have rocky outer shells and metallic cores. The four outermost planets are vastly different and each possess their own identifiable features. Scientists have studied the process of planetary formation in hopes of grasping how our solar system came to be, but the answers have not been simple.

"Looming over all the attempts to explain planetary diversity, however, is the chilling specter of random chance," wrote Richard Kerr, a staff writer at Science. "Computer simulations show that the chaos of caroming planetesimals in our still-forming planetary system could just as easily have led to three or five terrestrial planets instead of four."

But the search for alien worlds could help scientists hoping to gain insights into the planets closer to home.

"Help might come from planets orbiting other stars," Kerr wrote. "As exoplanet hunters get beyond stamp-collecting planets solely by orbit and mass, they will have a far larger number of planetary outcomes to consider, beyond what our local neighborhood can offer. Perhaps patterns will emerge from inchoate diversity."

Why is the sun's corona so hot?

The sun's ultrahot outer atmosphere is called the corona, and it is typically heated to temperatures ranging from 900,000 degrees Fahrenheit (500,000 degrees Celsius) to 10.8 million degrees F (6 million degrees C).

"[F]or the better part of a century, solar physicists have been mystified by the sun's ability to reheat its corona, the encircling wispy crown of light that emerges from the glare during a total solar eclipse," Kerr said.

Astronomers have narrowed down the culprits to energy beneath the visible surface, and processes in the sun's magnetic field. But the detailed mechanics of coronal heating are currently unknown.

"Just how the magnetic field transports the energy is much debated, and how the energy gets deposited once it reaches the corona is even more mysterious," Kerr wrote.

To see Science's full report on the greatest mysteries in astronomy today, see here:http://www.sciencemag.org/site/special/astro2012/index.xhtml

DISCUSSION

GROUP

DISCUSSION

GROUP

Write a comment